The American Spelling Book came out in 1783. Reprinted many times – including in cheap editions with a blue binding, used widely in schools – it sold a staggering ten million copies by 1829. The book begins by teaching the alphabet, then the different sounds of vowels and consonants, on to syllables, simple words, complex words, and full sentences.

Webster’s Spelling Book sought to standardize spelling. Browse old diaries or letters to see how inconsistently people used to spell: “plese” for please, “cityzen” for citizen, “suckceed” for succeed, “croud” for crowd, and so on.

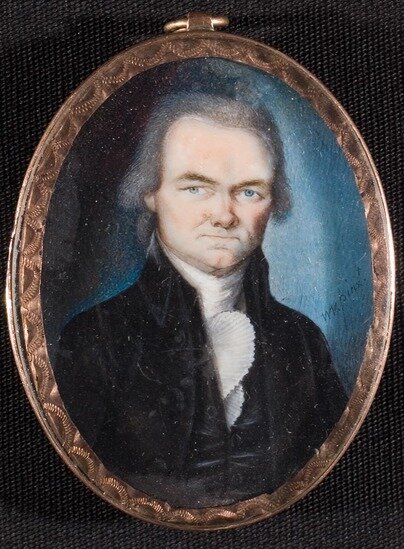

The Connecticut-born, Yale-educated Webster published his speller when he was 25 years old and teaching school. Forty-five years later, in 1828, he brought out his magnum opus, the comprehensive American Dictionary of the English Language, the book for which he is best known. For most 19th-century Americans, “Webster’s” became synonymous with “dictionary.”

According to historian Jill Lepore in A is for American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States, Webster believed that “America could never be fully independent from England, or fully united as a nation, without its own peculiar but common tongue.”

Some scholars suggested we should all speak and write in Greek, Latin, French, or Hebrew. Webster felt we should stick with English but shape it into an “American language” that would become “as different from the future language of England, as the modern Dutch, Danish and Swedish are from the German, or from one another.”

In researching his American Dictionary, Webster spent a year in Europe, where, writes Lepore, “he would pore over crumbling pages at the British Museum and the Bibliotheque Nationale, trying to track down the elusive origins of words.” It took him 26 years to complete the book; he is said to have learned 28 languages, including Old English, German, Spanish, French, Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and Arabic – because, of course, a dictionary should present the linguistic origins of words as well as defining them and specifying how to spell and pronounce them.

Differences in pronunciation between Northerners and Southerners, said Webster, “afford much diversion,” with many people making fun of how their fellow Americans spoke. (My main character Gideon gets mocked a lot because of his Pennsylvania Dutch accent.) Webster observed that “a habit of laughing at the singularities of strangers is followed by disrespect” and that “our political harmony is therefore concerned in a uniformity of language.”

Webster’s dictionary included 70,000 words, of which 12,000 had never appeared in a published dictionary before. He made sure to add American words like “skunk” that didn’t show up in dictionaries in England.

Unlike his fabulously popular speller, sales of the more-expensive dictionary lagged. Webster mortgaged his home to raise funds for a second edition, leading to financial difficulties during the final years of his life. He died on May 28, 1843, at the age of 84. His last rather erudite words were “I am entirely submissive to the will of God.”

During his life, Webster rubbed plenty of people the wrong way. “You may read Pedant in his very phiz,” wrote the playwright William Dunlap. Others called him “a self-exalted pedagogue,” “an incurable lunatic,” and “full of vanity and ostentation.” Lepore labels him “a failed schoolmaster, a passable flutist, a lousy lawyer, an intriguing essayist, an inexhaustible lobbyist, a shrill editor, a pompous lecturer,” and “undoubtedly also a prominent American citizen and, to many Americans, an eminent and admirable man of letters.”

The poet Emily Dickinson doted on her 1844 edition of Webster’s, calling it her “only companion” for years. According to a Dickinson biographer, “The dictionary was no mere reference book to her; she read it as a priest his breviary – over and over, page by page, with utter absorption.”

As a devotee of words, I enjoy reading in my dictionary. And I love writing in English, rich and versatile thanks to its adoption of words from many different cultures and tongues. Noah Webster helped form the English language into an American way of defining, writing, and thinking. For that, we are in his debt.